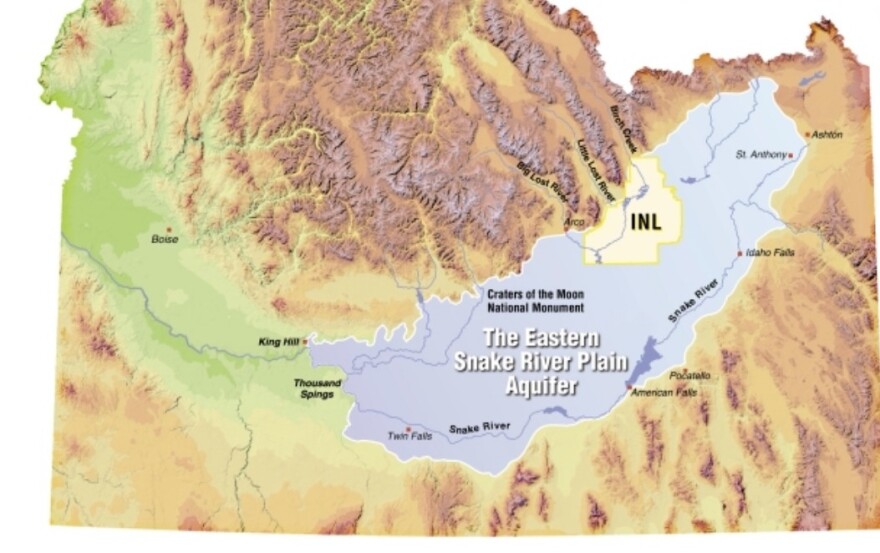

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) this week released several reports on important aquifers around the country. Idaho’s Snake River Plain Basin features in two of those reports. About a fifth of Idahoans rely on that aquifer as their only source of drinking water.

USGS hydrologist Kenneth Skinner says the Snake River aquifer is one of the cleanest in the country, but pollution has been growing. The biggest culprit is nitrate from agricultural fertilizer and dairies. In drinking water, nitrate can cause serious health problems, especially for the very young.

Most of this vast expanse of subterranean water has elevated nitrate levels, but only about 4 percent of the spots the USGS has been keeping tabs on have levels that exceed drinking water standards.

“The areas where we found the greatest nitrate concentrations is around the Paul and Minidoka area,” Skinner says. “There’s a lot of nitrogen inputs coming in that area, but the ground water there is just moving along slowly. So those nitrogen inputs have time to hit the ground water table, and start working their way down into depth were the pumps are for people.”

Skinner says the pollution increase is slowing because farmers are improving their practices. But it can take a long time for existing nitrate to leave the groundwater supply.

“One scenario we ran was if they all just quit farming and the dairy men all went away, how long would it take to show up in the ground water?” Skinner says. “And in [Minidoka County] it was about 40 or 50 years to see a change in nitrate concentration.”

Of course agriculture is not going to stop in the Snake River Plain. And according to some of Skinner’s previous studies, within 30 years or so a bigger slice of Minidoka County as well as some of Twin Falls County around Buhl could have undrinkable water.

Find Adam Cotterell on Twitter @cotterelladam

Copyright 2015 Boise State Public Radio