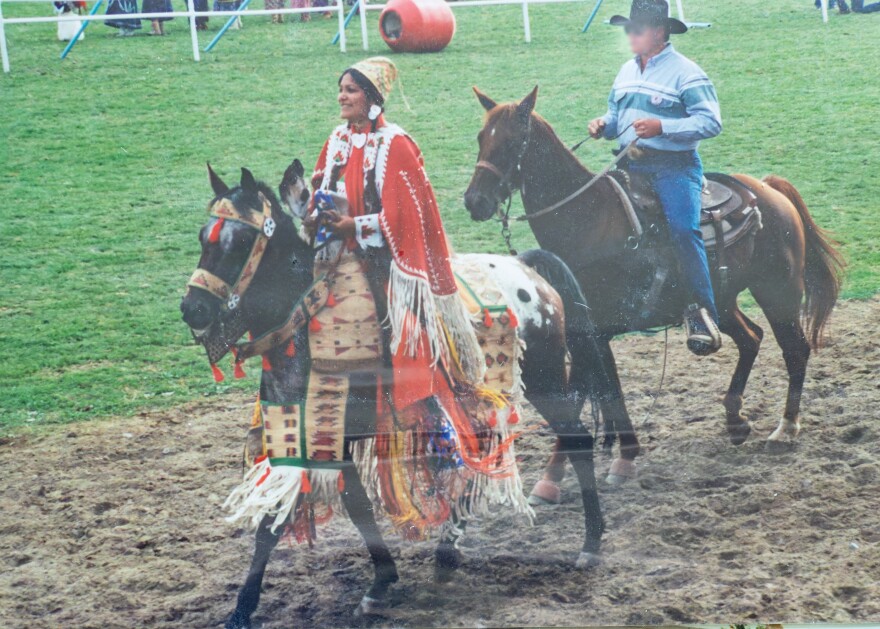

Ornately-beaded attire is an important aspect of Nez Perce tribal gatherings and parades – even for horses. The tradition of hand sewing horse regalia goes back generations. Horses are often draped in keyhole shaped head pieces, beaded saddle drops and decorative martingales at the chest.

Nez Perce artist Lynnette Pinkham continues to pass down knowledge of the traditional art to her niece, Jackie McArthur. The two assembled full horse regalia for McArthur’s daughter to use during her reign as a Happy Canyon Princess for the Pendleton Round-Up last year.

Pinkham grew up in Lenore, surrounded by grandparents and elders who taught her Nez Perce traditions, such as how to sew wing dresses, war shirts and shawls with long fringe – her specialty. They also taught her to ride horses at tribal events, bead moccasins and weave corn husk bags. Pinkham dutifully listened and internalized a vast archive of knowledge about her people’s ways.

“I was lucky to have a lot of grandmothers and I saw this work being done every day,” Pinkham said. “I watched it from the time I was little and I'm still learning. We give this culture to our children.”

McArthur remembers learning how to sew traditional garments years ago from finishing Pinkham’s projects. Pinkham would start production on a stack of shawls and then drop them with McArthur to learn the process and finish.

McArthur is descended from the Okanagan, Arrow Lakes and Colville people of the Columbia River. About 23 years ago, she moved to PyNimAh, an area above the Clearwater River at the northern edge of the Nez Perce Reservation. McArthur and her husband raised their children on the family land, close to her husband’s family, which includes Pinkham, of Lenore.

McArthur said when it comes to clothing for special events, there’s a very structured dressing protocol in their culture. Dresses should fit properly to fully cover arms and legs.

“For funerals an elder or the family can say, 'If you have a buckskin, you need to wear it. And if you don't have a buckskin, you wear a shell dress. And if you don't have a shell dress, you wear your wing dress,’” she said.

That dressing protocol also applies to horse regalia. In addition to being able to sew, McArthur also beads – a skill that gave her a head start for learning the art of horse regalia. She’s honed her craft over the years through trial and error. She remembers the first piece she beaded: a choker necklace, which she now recalls as looking “crazy.”

Since then, she’s beaded moccasins and baby boards for her family members. She found her children preferred her homemade accessories to anything purchased.

“It just depends on what the family needs is what my art form is,” said McArthur.

Last year, that need became beading horse regalia. When her daughter, Lauren Gould, was named one of the 2024 Happy Canyon Princesses, McArthur felt prepared to work late into the night. She hand-beaded the elaborate regalia required to participate in rodeo court activities, such as riding in parades and giving awards at the rodeo.

“I never envisioned myself making horse trappings. I'm not a horse person. We don't have horses, but our daughter rides. Because I can bead and because I can sew I'm able to do it, but I'm really learning about the significance of the trappings.”Jackie McArthur

Luckily, she had Pinkham to guide her through the process of assembling a horse regalia. They incorporated a mix of heirlooms from their family and friends and newly made pieces to match what they already had. Pinkham is a longtime veteran participant herself of the Round-Up Parade and the vaudevillian Happy Canyon Night Show. Each year, she camped with her family in the tepee village that sprung up next to the rodeo arena.

Pinkham and McArthur received funds from the Idaho Commission on the Arts to support their efforts. Pinkham, an experienced horseback rider, imparted valuable techniques for making each piece and provided tips on how to care for a horse that will wear regalia and the etiquette surrounding the tradition.

“It's not like you can just go out and throw an outfit on a horse,” said Pinkham. “Not all horses will accept it.”

Pinkham said it’s important to desensitize horses to wearing various types of attire, which includes everything from feathers to bells.

In her day job, Pinkham worked at the Nez Perce National Historical Park’s visitor center and museum as a Museum Specialist and Technician, where she archived, organized and shared their collection of Nimíipuu artifacts with the public.

She found inspiration each day, combing through rare and historic moccasins, baskets and clothing to build exhibits that feature her people’s culture. Pinkham also commissioned artisans in her community to create new work to demonstrate traditional regalia and customs, including an example of a traditional full horse regalia on display at the entrance of the building.

Both women proudly share the museum exhibits with outsiders to educate others about their culture. The regalia exhibit shows an example of how Nimíipuu men dressed their horses. A wooden horse manikin is masked by a red felt hood with holes for the ears, eyes and mouth. Yellow, pink and blue flowers bloom from the corners and sawtooth green edges line the neck opening. A spray of feathers is mounted on the forehead.

“Each different piece has a name for it. There's also pieces that a male rider will use and a female rider will use,” McArthur said.

Pinkham and McArthur took a lot of inspiration from the museum exhibit's traditional regalia to inform the making of their own. The female-specific collection would include a keyhole head piece beaded sky blue with a red and gold triangle pattern and a matching martingale at the chest, beaded decoration for the back as well.

For women’s horses, there was a horse blanket as well as a rare Nez Perce saddle, which rises 10 inches in front and behind the rider.

“That's where the baby board is attached,” said Pinkham. “Sometimes there'll be things tied on the back of the horse, whether it's beaded bags, berry baskets or the digging bags.”

Traditionally, women’s horse regalia also featured long fringe draped over the rump of the horse. Pinkham said the fringe signified that a woman’s family had a prominent hunter. She emphasized the importance of using heavier elk leather for this part.

“Now we use elk hide because we don't have that access to buffalo like we used to,” she said. “The buffalo fringe was heavier and it had that more of a sway feel when the horse would walk.”

McArthur worked on the martingale with Pinkham — they adapted a design from an heirloom bag that her daughter would also wear as a part of the regalia. The base and side straps of the martingale are red wool, with bells and metal spots to weigh the piece down. The beaded center incorporates chevrons that mimic the feathers of an arrow and the sáplis – a Nez Perce symbol that represents a whirlwind or the Big Dipper constellation.

The two put the design on graph paper and then McArthur beaded on top. She said the beading presented some challenges. She had difficulty finding contemporary bead colors that would match the vintage bag they based the design on. She was better prepared for other challenges.

“You have to know how to tie knots. You have to prepare your thread. You have to have the correct needle. You have to pay attention to the placement of your thread. These are called ‘tri cut beads,’ so they're sharp. You have to have a particular thread, otherwise your piece can just fall apart.”Jackie McArthur

Pinkham helped bring everything together, referring to her own family horse regalia collection and also those of the museum.

“When I see an old piece, especially if it comes out on the dance floor somewhere. I'll ask the person wearing it, ‘Can I look at your stuff?’” said Pinkham. “And if they allow me, then I look at it in detail.”

Completing the full horse regalia took months, but McArthur explained that regalia and traditional pieces worn during ceremony are really a life-long endeavor of maintenance and continually adding and rearranging. Reflecting on the apprenticeship, she said she’s glad she took the unexpected step to learn the art. The vision of her daughter using the regalia motivated her throughout the long process. Her efforts to do things correctly will prove worthwhile when the next generation needs to repair the regalia and looks back over her work.

“The end result is a beautiful thing to have available to and within the family,” said McArthur.

She hopes her example can inspire future generations to continue the rich tradition of Nez Perce horse regalia.

Expressive Idaho is produced by Arlie Sommer and edited by Sáša Woodruff. Original music in this story is by Jared Arave. The written article is by Arlie Sommer and edited by Corinne Ruff, Lacey Daley and Katie Kloppenburg. A transcript of the audio version of this story is available.

Expressive Idaho is made in partnership with the Idaho Commission on the Arts’ Folk and Traditional Arts Program with funding support from Dr. Suzanne Allen, MD, Jennifer Dickey and Andy Huang. This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Jackie McArthur's last name.