Imagine a weekday morning on State Street: A commuter leaves her newly built apartment in a four-story building along State that replaced an aging strip mall. She walks a few blocks to a bus stop. An electric sign shows how soon the next bus will arrive. The buses run every 15 minutes or more.

The bus arrives in a dedicated bus lane and pulls up to the boarding platform, which is above the street and level with the bus’ entry door, making it easy for everyone — even those with wheelchairs and walkers — to board.

This is the future that regional planners envision for transportation and development along State Street, one of the most widely traveled east-west routes in the Treasure Valley.

As State Street becomes more congested, local agencies are planning sweeping improvements between Whitewater Park Boulevard in Boise and Highway 16 in Star. The plan, which has been 15 years in the making, would bring higher-density development and faster, more frequent public transportation with the creation of a bus rapid-transit system.

Planners call it “transit-oriented development.”

“The transit supports the land use, and the land use supports the transit,” said Daren Fluke, Boise’s deputy director for comprehensive planning, in an interview.

Public transportation needs density to survive. Few today would call State Street dense. The street is littered with used-car dealerships, drive-through restaurants, 60s-era strip malls, gas stations, and billboards for injury lawyers.

Mostly, State Street is asphalt. Swaths of gray parking lots make it clear what this street is built for: the car.

“Buildings here are starting to age,” Fluke said. “A landowner could very well say, ‘There’s a higher and better use for this property than what I’ve got here today.’ They could start to provide additional land uses that create additional housing.”

Redeveloping State Street

The transformation would be slow. Planners have identified four intersections, or nodes, along the No. 9 bus route they where they want to focus redevelopment: Whitewater Park Boulevard, Collister Drive, Glenwood Street and Horseshoe Bend Road.

Each node would be designed as a dense, walkable neighborhood: More crosswalks and wider sidewalks. Two- to four-story buildings with ground-floor retail and apartments above. Parking lots located behind businesses rather than facing the road.

There are some major roadblocks. Even as Boise’s planners charge forward, many of the plans they’ve drawn up couldn’t be built today under the city’s current zoning ordinance.

Last year, Boise hired a consultant to update its zoning code. City planners say they hope to eliminate some requirements for parking, setbacks from the street and height limitations. The process could take more than a year.

Then there’s the question of paying for the public share of the improvements. Under former Mayor David Bieter, Boise was working to create a new urban renewal district along State Street between Whitewater Park Boulevard and Horseshoe Bend Road.

Boise already has five such districts, which freeze property taxes that the city and other local taxing jurisdictions collect on properties within the district. For 20 years, any new property tax revenue generated by new development or higher property values goes to the urban renewal district to be spent on public improvements.

Mayor Lauren McLean, who took office in January, has not said whether she will continue with those plans, though she likes the idea.

“That’s one of the districts that we need to have a robust public process around before it’s designated,” she told the Statesman in an interview. “I believe in the importance and power of urban renewal as a tool to invest in our neighborhoods, especially in this corridor. It creates the possibility we could have a transit system that moves our residents from home to work.”

Build More Housing

Already, some higher-density housing projects are underway along the corridor.

Roundhouse, a Los Angeles firm with a Boise office, is building The Clara in Eagle . It will include 277 apartments and townhouses west of Linder Road and just south of State Street.

CEO Casey Lynch says projects like his are rare, though. It’s more expensive to build dense apartment projects than suburban-style apartments surrounded by surface parking on former farmland in a city like Meridian.

“Now, it’s not that inconvenient to commute and drive,” Lynch said. “But if the inconvenience changes, then renters will be willing to pay more of a premium to live in an infill location.”

New apartments built on State Street would cost about the same to construct as apartments downtown. With land selling at prices similar to downtown’s, unsubsidized rents would be similar to downtown’s too — around $1,500 a month for a one-bedroom. Rents further from Boise would likely be cheaper. A one-bedroom at The Clara is expected to rent for close to $1,050 a month.

Market rents need to be that high to make a project pencil out for a developer, said Boise developer David Wali.

“The problem with a lot of the real estate out there is that it’s already too valuable to repurpose,” he said. “You’d need to have a significant increase in overall rents to justify tearing down a building and repurposing it with apartments.”

A market analysis conducted by the city of Boise agreed. The analysis found that that the rents a developer could get in today’s market are too low, and the land prices too high, for a developer to justify building on State Street.

“If there were public transportation, that might change that calculus,” Lynch said.

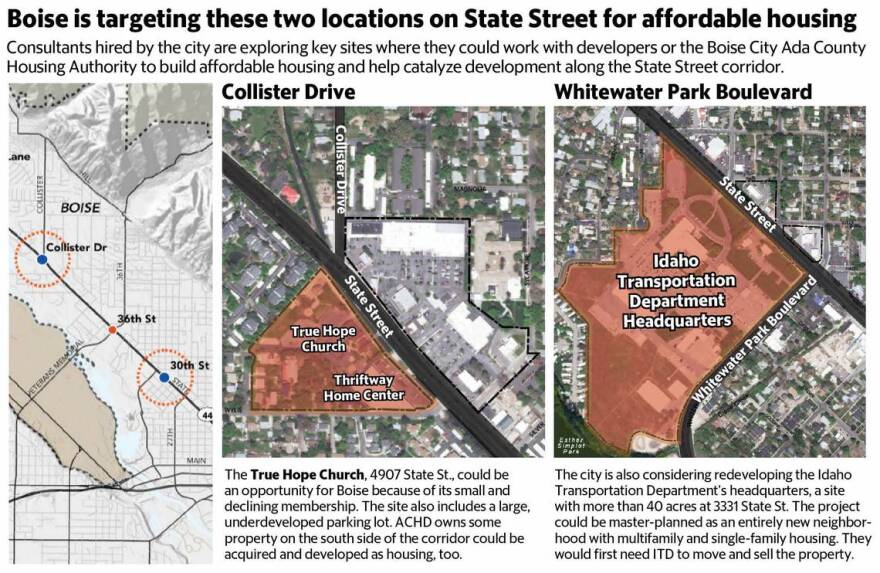

Boise hopes to catalyze development along the corridor with subsidized housing that would rent below market-rate. Already, Boise consultants have identified parcels near Collister and Whitewater Park boulevard s that they could redevelop in partnership with private or public developers.

Improving Public Transit

In part, State Street is an ideal spot for development because it is already so busy.

Forty thousand cars pass through State Street’s busiest intersections every day. The No. 9 route along State Street is also ValleyRide’s most popular route, with 900 boardings each day, or around 450 people.

Shannon Lind is one of them. By 7:30 a.m. each morning, Lind leaves her house near Chinden Boulevard and Eagle Road. She drives to the parking lot at Big Lots on State and Glenwood streets, which has become an informal park-and-ride for bus riders like her who hop on at the end of the line.

If it’s not late, the bus arrives by 7:45 and, depending on weather and traffic, drops her off between 8:10 and 8:20 at the Main Street transit center downtown where she walks to her job as a project manager at U.S. Bank, right above the station.

“It’s a great route for me, because I have a flexible schedule,” Lind said.

Not everyone has that flexibility. Transportation planners want to make the bus service faster and more frequent so more people will use it.

“We’ve seen that when we do increase the frequency of service, making it easier for people to get on the bus and to their destination, our ridership does go up,” said Stephen Hunt, principal planner for ValleyRide, which operates the bus system throughout the Treasure Valley.

ACHD, Boise Go Back And Forth On Street Design

The need for more capacity on State Street became apparent in 2007. Planners predicted that if they didn’t act, commute times would double between downtown Boise and neighborhoods to the west.

The most obvious solution was to widen the road to nine lanes from five. But to do so would have required using eminent domain to buy right of way, including some existing businesses along the road.

There was also the problem of induced demand: the idea that increasing the capacity of a roadway gives more people a reason to drive, ultimately defeating the original goal of reducing traffic jams.

“Nobody had the stomach to say, ‘Let’s widen State Street to nine lanes,’” Fluke said. “We all acknowledge that just building a bigger road for cars is not getting us where we need to be. We need to be thinking about moving people and not just moving cars.”

Together, the city of Boise, ValleyRide, and the Ada County Highway District — which controls local roads — decided to widen the street to seven lanes, and design it for faster bus transit on the outer lanes.

But now, ACHD and the city of Boise aren’t on the same page about how to accomplish that.

The highway district envisions using the outer lane for any high-occupancy vehicles, including buses and carpools.

The city of Boise wants to dedicate the outer lanes to a bus-rapid transit system . By reserving a lane exclusively for buses, the buses can move faster than the cars backed up in neighboring lanes. To save more time, the buses stop right in their lane, rather than pulling out of traffic to stop and then merging back in. In-lane stops have been shown to reduce the length of a stop to 15 seconds from 45 seconds.

Eugene, Oregon and Los Angeles have opted for bus-rapid transit over rail, because it’s cheaper and can operate on existing infrastructure.

Both proposals face legal hurdles. The highway district says it cannot use its budget to build a lane exclusively for bus travel, as that would undermine its mandate under state law, which is to provide for vehicular movement. If ACHD is funding an additional lane, it must allow for cars — at least sometimes, the agency contends.

ACHD’s own proposal for high-occupancy lanes is not currently allowed under state law, except in counties with populations of fewer than 25,000 that have resort cities inside their boundaries.

Fluke advocates a compromise: Dedicate the outer lanes as a business-access transit corridors, which would be reserved for buses and right-turning vehicles.

ACHD hasn’t agreed to anything yet, said Ryan Head, the agency’s supervisor of planning and programs.

The agency has begun to widen State Street, starting at major intersections like Veterans Parkway and Collister Drive. Widening the stretch in between those to seven lanes would cost about $15 million per mile. Head said ACHD won’t fund that work until traffic increases to 43,000 vehicles per day from 40,000 and ridership on the No. 9 route increases to 1,500 daily trips from 900.

Today, the State Street route runs weekdays from 5:15 a.m. to 9:15 p.m. with 15-minute service for 5 hours a day during peak commute hours and 30-minute service the rest of the day. Over time, planners hope to run a bus between Glenwood and Downtown Boise every four minutes during rush hour, with 15-minute service along the rest of the route.

Public transportation funding by population Boise peer cities

Finding Funding For Valley Ride, Road Projects

Located in a metropole that spends less on public transit than its peer regions, ValleyRide is challenged in come up with the funding to make the improvements they want.

Widening the seven miles of State between Whitewater Park Boulevard and Horseshoe Bend Road would cost about $185 million. Beyond that, the new stations and platforms, plus the cost of planning, could range from $25 to $65 million — and that’s all before the operational costs. Unless the state creates a new funding source for public transportation, ValleyRide can only increase bus frequencies when cities contribute more, Hunt said.

Most of ValleyRide’s $17 million yearly budget comes almost from city contributions, with Boise chipping in the most.

This year, Boise allocated $8.6 million for ValleyRide, which includes an additional $1 million that will go, in part, to expand 15-minute service on State Street to a little over six hours each weekday. Eagle also upped its contribution to ValleyRide this year, which will extend the route to Ballantyne Lane with 30-minute service. The service changes start in April.

ValleyRide hopes to leverage local funding to apply for federal grants that will buy more buses and improved stations. ValleyRide is working with ACHD to determine if it can use some ACHD funds to build the modern stations proposed along State.

The bus system would be a major investment, but it’s small compared with the estimated $2 billion that Treasure Valley residents spend every year on their cars, auto insurance, maintenance and gas, Hunt said.

Nearly three-quarters of Treasure Valley residents say they want more public transportation options. Still, ridership has declined on ValleyRide as even as the local population has grown.

The Journey To Better Transit: A Bumpy Road

At 3:15 p.m. on a recent Thursday, it doesn’t feel like ridership is decreasing. The No. 9 bus, already packed with commuters who boarded at the Main Street Station, stops at 11th Street, where a flood of Boise High students board. The bus driver shouts at them: “Keep moving back, please!”

Shannon Lind, the U.S. Bank administrator, is pressed up against the window in the back.

“Improving the corridor — that’s ahead of the game,” Lind said. “The transit system itself needs to be improved before they add all these bells and whistles.”

That sentiment is shared by riders like Elizabeth Jacox, who last year saw the bus route through her neighborhood cut back on its schedule. That was a problem for Jacox, who shares a single car with her husband. Now, to take the bus to her office downtown, she has to walk 15 minutes from her house in Northwest Boise to State Street to board the No. 9, which takes 20 minutes to get downtown from Gary Lane.

“For me, it’s about bringing a route through my neighborhood,” she said.

Fluke hopes that the improvements Boise makes on State Street will increase ridership, thus allowing ValleyRide to further scale the bus system.

“With transit service, you’re always in a chicken and an egg scenario,” he said. “People don’t use the service because it’s lousy, and so how do you ever upgrade the service when no one’s using it? It does take a leap of faith, that if you provide better service, then people will use it.”

Transforming the entire corridor with dense development and the transit line would take a concerted effort from the disjointed agencies critical to the project — the Ada County Highway District, ValleyRide, and Boise, Eagle and Star. But if history is any indicator, coordination among them won’t be easy.

A unified vision moving forward can help, though, Fluke said. “We’re acknowledging that we can’t build ourselves out of traffic congestion.”

This story was produced by the Idaho Statesman in collaboration with Boise State Public Radio.