This project was powered by America Amplified, a public radio initiative.

The Mountain West News Bureau series "Elevated Risk" spotlights police violence across the region. Here's an FAQ about our reporting and the data behind it.

Where do the data on police killings come from?

How is a "police killing" defined?

How are you defining the Mountain West?

Why did you look at the per capita rate of police killings?

How did you deal with multiple years of data?

How does the Mountain West compare with the U.S. in terms of police killings?

How does the Mountain West compare to other regions in the U.S. and over time?

How do individual states compare with each other?

What role does race play in fatal encounters with the police?

What about police who are killed in the line of duty?

Where can I get the data from your analysis?

This reporting project began with a question: Are people in the Mountain West more likely to be killed by police than elsewhere in the United States? To answer this question, we conducted an analysis of several databases of police killings in the U.S. We also looked at data on racial and socio-econmic demographics, police deaths, and police killings in other countries. This FAQ covers what we learned and how we conducted our analysis, as well as the limitations of the data and what it cannot tell us about police violence.

Where do the data on police killings come from?

The FBI does collect and publish data on the use of police force, including police killings, under a system that was recently overhauled. (The FBI's previous data collection system, justifiable homicide reports, were notoriously sparse and unreliable. For some primers on the unreliability of data on police killings, check out these articles from Washington Post, Nature and Marketplace.) Police agencies voluntarily submit this data: The FBI's 2019 use-of-force data, the first year under this new system, covers agencies employing only 41% of U.S. police officers.

To fill this data gap, several independent organizations have compiled and published their own databases. In our analysis, we used databases from two independent research collaboratives (Fatal Encounters, Mapping Police Violence) and two news organizations (Washington Post, The Guardian). Each of these data collection projects uses a slightly different methodology to track and verify incidents by combining police reports, public records requests, media reports, and crowd-sourcing. Each of these datasets has limitations and none is comprehensive.

We also considered data from Canada and the U.K. The Canadian government does not track fatal encounters with police, but the CBC has compiled its own database based on media reports and public records. In the U.K., police killings are tracked by the Independent Office for Police Conduct.

How is a "police killing" defined?

Determining whether a person is killed by the police is complicated: Does it include people who die in car crashes while being pursued by police, or people who die by suicide while in police custody? What about fatalities from a heart attack or drug overdose? Each of the U.S. datasets we used has a distinct definition of what constitutes a fatal encounter with the police:

- Fatal Encounters: "...non-police deaths that occur when police are present or are precipitated by police action or presence. Officer deaths are included when caused by another officer."

- Mapping Police Violence: "...a case where a person dies as a result of being shot, beaten, restrained, intentionally hit by a police vehicle, pepper sprayed, tasered, or otherwise harmed by police officers, whether on-duty or off-duty."

- Washington Post: "...only those shootings in which a police officer, in the line of duty, shoots and kills a civilian...not tracking deaths of people in police custody, fatal shootings by off-duty officers or nonshooting deaths."

- The Guardian: "Any deaths arising directly from encounters with law enforcement. This will inevitably include, but will likely not be limited to, people who were shot, tasered and struck by police vehicles as well those who died in police custody. The database does not include suicides or self-inflicted deaths including drug overdoses in police custody or detention facilities."

Fatal Encounters' definition is the broadest. Washington Post's – which only covers fatal shootings – is the narrowest. For our analysis, we also filtered out vehicle crashes from the Fatal Encounters database to create a fifth database: Fatal Encounters without vehicles.

Due to differences in how police killings are defined and how the data is collected, these databases are not directly comparable. Thus we considered all of these databases in our analysis of how the Mountain West compares to the rest of the U.S. in order to see whether they align.

How are you defining the Mountain West?

In our analysis, we used the U.S. Census Bureau's geographic designations to compare regions and sub-regions, which the Census calls "divisions." When we refer to the Mountain West, we mean the Mountain division within the West region, which consists of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Why did you look at the per capita rate of police killings?

To be able to compare police killings in the Mountain West region of the U.S., which has about 25 million people, with the U.S. as a whole, which has about 329 million people, we calculated per capita rates of police killings. To do this, we divided the number of police killings by the population. All population data in our analysis is from the U.S. Census Bureau. Because the rate of police killings is very low, we report it as the number of people killed per million people in the population.

How did you deal with multiple years of data?

Each of the police killings databases we used covered a different time series:

- Fatal Encounters: 2000 to present

- Mapping Police Violence: 2013 to present

- Washington Post: 2015 to present

- The Guardian: 2015 to 2016

We looked at the per capita rate of police killings for each year individually and visualized this data over time to determine whether the rate of police killings in the Mountain West are anomalies or longer term trends.

Because the number of police killings is small compared to the size of the population, variation year-to-year could potentially produce large swings in the per capita rate. To address this, we also combined multiple years of data together to average our year-to-year fluctuations. We considered several time periods in our analysis (i.e., 2010 to 2020, 2015 to 2020) and indicated which time period we are referring to in our results and visualizations. When calculating combined-year average per capita rates of police killings, we added up the police killings over the entire time period (i.e., all police killings in Montana from 2015 to 2020) and divided it by the population over the entire time period (population each year, 2015 to 2020). We did it this way (as opposed to averaging the annual per capita rates) so that year-over-year changes in population would not skew the average.

How does the Mountain West compare with the U.S. as a whole in terms of police killings?

From 2015 through 2020, the Mountain West region had the highest rate of people killed by police, per population, of all regions in the U.S. This is true for all five of the databases we analyzed (summarized in the table above). Looking at the Fatal Encounters dataset, without vehicular incidents, in the Mountain West 1,131 people were killed by police from 2015 to 2020. That's an average of 7.74 people killed by police per million residents each year. In comparison, nationwide 8,574 people were killed by police from 2015 to 2020, an average of 5.48 people killed by police per million residents each year.

We found that the difference in rates of police killings between the Mountain West and the rest of the U.S. was large and statistically significant. For example, in 2020 the mean rate of people killed per million residents in the Mountain West (averaged across states) was 9.81 fatalities per million (with a standard deviation of 2.9); in non-Mountain West states, the mean was 4.48 fatalities per million (with a standard deviation of 2.1). We ran a t-test – which evaluates whether two populations are distinct – between the Mountain West and non-Mountain West states, and got a p-value < 0.001, which means that the chance that the differences between the two groups of states is due to random chance alone is extremely low.

How does the Mountain West compare to other regions in the U.S. and over time?

We also considered how the number of people killed by police changed over time. This plot shows the Mountain West (in magenta) compared with the U.S. (in dark grey) from 2000 to 2020, along with other geographic regions (light grey). Starting in 2009, the Mountain West has had more police killings per million residents than the U.S. Since 2015, the Mountain West has, on average, also had more police killings per million residents than any other region.

How do individual states compare with each other?

We ranked states according to their average rate of people killed by police, 2010 to 2020, in the graphic below, which includes the average over this entire time period (large dots in the center of each row) and each individual yearly average (smaller dots), so that you can see the range of values in each state. New Mexico has the higher average rate of people killed by police in the country. Nevada, Arizona, Colorado and Montana were also in the top 10.

What role does race play in fatal encounters with the police?

Analyzing race data is tricky.

Data on the race of people killed by police is often unavailable. When race data does exist, it is often unreliable, because it may be compiled from police or media reports rather than on the victim's self-identified race. For example, of the 1,533 non-vehicle fatalities from 2020 in the Fatal Encounters database, 565 (37%) did not have race information. The percent of cases where race is unknown is lower in the Mountain West than in the rest of the U.S., but it is still sizable, ranging from about 10 to 20%. (Fatal Encounters also imputes race based on other details about each incident, but we did not use these imputed values.)

Further, the racial and ethnic categories that the Census Bureau uses does not line up exactly with the racial and ethnic categories that Fatal Encounters uses. For example, Fatal Encounters has a "Middle Eastern" label, which the Census does not; Fatal Encounters combines Asian and Pacific Islander into one category, whereas the Census separates them. We lined up these categories as closely as possible.

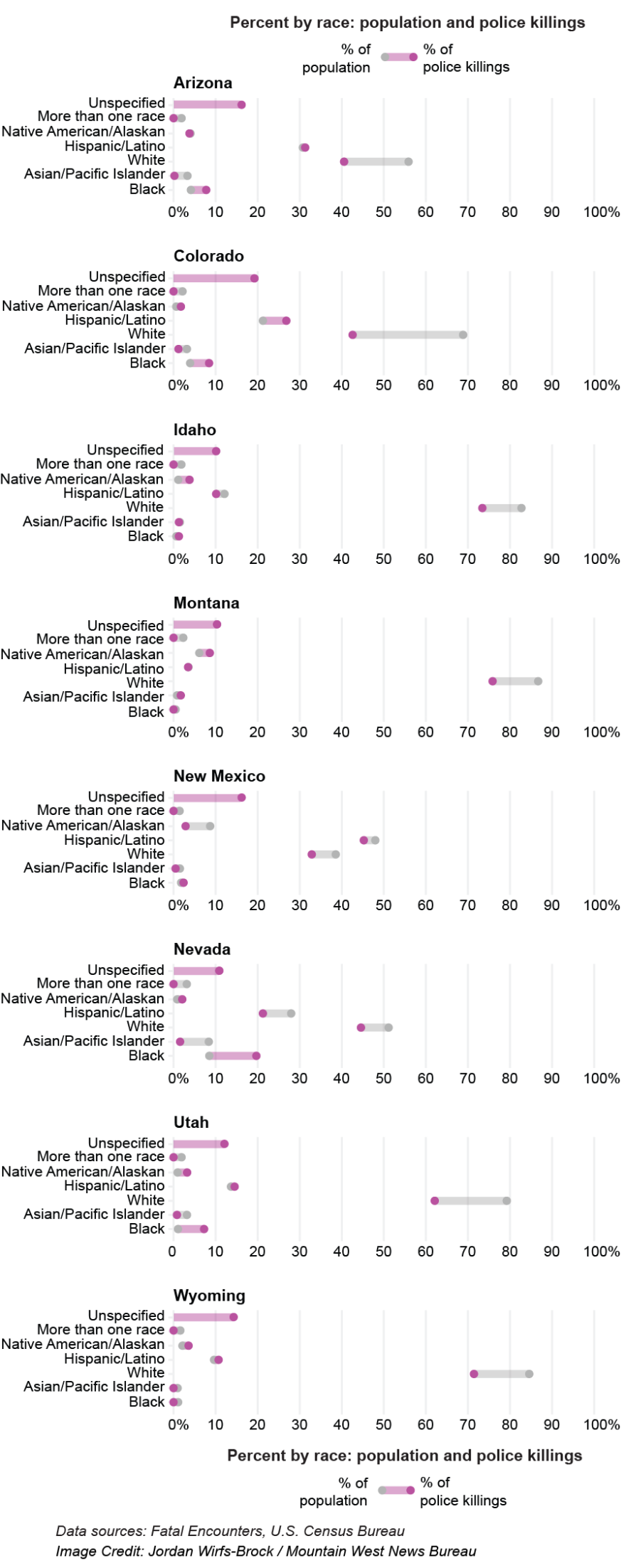

Thus, we tried to paint the clearest picture of the role of race in fatal encounters as we could, given that the data is murky and incomplete. In our analysis, we compared the distribution of fatal encounters with police, by race, to the distribution of the population, by race, to see which racial groups may be over or under represented.

The figure below contrasts the portion of the population in Mountain West states, by race, to the portion of police killings, by race. Each state also includes the portion of police killings where race was not specified. In this chart, we can see that the portion of police killings where the victim is white is consistently smaller than the portion of the population that is white. For example, in Colorado from 2010 to 2019, 68.9% of the population was white, but only 44.8% of people killed by police were white. Conversely, we can see that some racial groups are overrepresented in police killings. In Nevada, only 8.5% of the population is Black, yet 18.2% of people killed by police from 2010 to 2019 were Black.

Here are the rates of police killings, per million, by race for 2010 to 2019 in Mountain West states:

- Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.50 fatalities per million people

- White: 4.65 fatalities per million people

- Hispanic/Latinos: 7.11 per million people

- Native American: 7.38 per million people

- Black: 14.38 per million people

Remember, 15% of fatal encounters with police in the Mountain West were lacking race data. Despite the picture being incomplete, the partial data shows that Hispanic/Latino people are 53% more likely to be killed by police than white people, Indigenous people are 59% more likely, and Black people are more than 200% more likely to be killed by police.

The complexity of analyzing data by race also makes it difficult to get a clear picture of how many Native Americans are killed by police. Let's consider New Mexico, where 8.7% of residents are Native American, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Yet in New Mexico, just 2.9% of fatal encounters with police (excluding vehicles) were Native American. It would appear that Native Americans are underrepresented in fatalities. And yet, because we don't know the race of the victim in 16% of fatal encounters in New Mexico, this may not actually be the case. Further, Indigenous people have faced a long history of misrepresentation in data that is collected about them, by outsiders, rather than with and for them. The data sovereignty movement challenges this tradition and advocates for Indigenous communities to be involved in data collection efforts and to have the right to control and apply their own data.

What about police who are killed in the line of duty?

In addition to analyzing data about people who are killed by police, we also looked at data on police officers killed in the line of duty. We used data from the FBI's Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) program. Police agencies submit this data voluntarily to the FBI, thus it is not a comprehensive dataset. The FBI differentiates felonious deaths – "in which the willful and intentional actions of an offender results in the fatal injury of an officer who is performing his or her official duties" – from accidental deaths, and we focused on felonious deaths in our analysis.

We compared the rates of felonious deaths in the line of duty to the rates of people killed by police (normalized for population) at the state level. We found that there was a positive relationship between civilian and police deaths: when there are more fatal encounters with police, there are also more police killed. As a region, the Mountain West is above the U.S. average for both officer fatalities and civilian fatalities per million people. However, with the civilian fatalities, it is the highest region in the country, whereas with officer fatalities, it's not the highest. This relationship is visualized below in a scatterplot of people killed by police (per million) versus police feloniously killed in the line of duty (per million).

Where can I get the data from your analyses?

We are sharing the data from the core of this project – annual rates of people killed by police, from the various databases, normalized for population – for the entire U.S., individual states, and geographic regions in a GitHub repository as CSV files.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.