Second in the three-part series, "Saving Amache"

John Hopper grew up in Las Animas, Colorado. It’s a small town where everybody seems to know everybody. But Hopper’s mom made a connection that stuck with him long after his childhood.

“My mother worked with a former survivor, Emery Nomura, briefly, but she worked with them,” Hopper said. “His wife … worked in the silkscreen shop.”

During World War II, the Nomuras were held at Amache, a Japanese American internment camp near Granada, about 60 miles away from where Hopper’s family lived.

Hopper developed a fascination with social studies and got his first job teaching at Granada High School. That’s when he got an idea.

“We’re right next door,” Hopper said. “We're a quarter-mile away from Amache. And I thought, ‘Man, this is an ideal situation to do a living history project.’”

He started gathering interviews along with his students in the early 1990s. They talked with Nomura and he provided addresses of people they should contact for interviews. They didn’t hear anything for weeks.

“So I said, ‘Maybe we did it wrong,’” Hopper said. “And then somebody called us from Denver – a long distance – and I took it at the school and she said, ‘Well, I have the questionnaire in front of me.’ I said, ‘Oh, you got one of them.’ She goes, ‘No, we've been passing it around.’”

Survivors and descendants started sending family heirlooms and artifacts from the camp. Eventually Hopper and the students ran out of space on the high school campus, so they moved everything to a local building in town.

“Did I think it was going to be like this? No, not not in my wildest dreams,” Hopper said. “We've got so many artifacts, we have to shift stuff in and out, making new exhibits all the time.”

Today, the museum has close to 1,400 artifacts that shed light on a piece of local history – everything from a stringed zither called a Koto, to saké bottles, to a print from the silkscreen shop where Nomura’s wife worked.

“Every object in here has a backstory,” Hopper said.

And he remembers the details of every single one – including a playing card from an illustrator known for his images of pinups.

“There is a Alberto Vargas card in there,” Hopper said this fall as he showed off a photo album to a group of tourists. “It was given to a gentleman that was in the 7E block. I believe it was. All the women signed it for good luck.”

Hopper doesn’t get paid for this, however. For the last 30 years, he’s volunteered along with his students to bring the Amache museum to life – from giving tours to cleaning it.

“They run this,” Hopper said. “They open it up, they vacuum, they mop the bathrooms, clean out the trash, keep everything up and running.”

Hopper allows survivors to come back and tell their stories at the museum, too. Mitch Homma’s dad and several other relatives were imprisoned at Amache, and Homma has contributed a lot to the museum.

“On the cot over there, that's my father's blanket,” Homma said to the tourists. “There's a light colored blanket, too. The light colored blanket is from the Amache hospital. And so that was probably grandfather's blanket when he passed away.”

The work of Hopper and his students has sustained Amache for years, and it does not go unnoticed by Homma.

“Those are the local guys, boots on the ground that are caring for the sites,” Homma said. “I'm actually super-fortunate to have a great group of grassroot stakeholders caring for different parts of the site, different projects, large and small.”

A hidden history

Amache is taught in Hopper’s history lectures. But he said that isn’t always the case with other teachers.

“It was a travesty in history and a very offshoot kind of history because it's not covered,” Hopper said.

Russell Endo understands this sentiment. During World War II, his family was incarcerated at a camp in Arkansas. When he was hired by the University of Colorado-Boulder to teach Asian American studies back in 1973, he knew a trip to Amache would be in his syllabus.

“I think it's important to actually be at the place where people have experiences that they're trying to learn about,” Endo said.

When he first started teaching about Amache, he said most of his students were of Japanese descent, so they were very enthusiastic.

“I think they were anxious to learn about where their families had been during the war or where their friends' families had been or other people that they knew,” he said.

Over time, as other students joined his class, there were different responses.

“Most of them had never heard about Amache and didn't actually know very much about Japanese Americans,” Endo said. “So I think the impact on them was much greater in terms of surprise and maybe dismay.”

Endo has since retired from the university, but he liked to give his students some questions to wrestle with, such as, “Who is considered an American?” He would also illustrate lessons with demonstrations, such as bringing in a copy of the Constitution and ripping it up. He said these concepts are important to understanding Amache.

“The stuff is just on paper, your rights don't exist unless people are enforcing them,” he said. “So what happened during World War II was a failure to enforce constitutional rights. And then we get into a discussion about how do people do this? And, you know, whether we're not doing this today.”

Endo has been working with some Denver-area public schools to add information about Amache to their curriculums, and he is set on seeing more schools do it. More importantly, he wants people to continue learning about Amache outside the classroom.

Digging up the stories

Hopper and Endo aren’t the only ones working to educate people about Amache. Bonnie Clark, an archaeology professor at the University of Denver, has been working at the site since 2008 to find artifacts that may have been left behind.

“We sort of walk back and forth across the surface of the site looking for remains of the things that people did to improve their life in camp,” Clark said. “The finds of that original work pointed out to me, you know, the ways that people were really kind of turning this place from a prison into a town.”

One big find was remnants of an ofuro. It’s a traditional Japanese bathtub that farm families would use to wash up. Those held at Amache built their own with cinder blocks because the camp only provided showers.

“It's one of the many ways that we've seen where people were, again, trying to sort of reclaim those things that make you feel human,” Clark said.

She excavates the site with her students, but also allows survivors to join her. Clark said these places and objects are like a time machine that helps survivors connect their stories to the bigger picture of history.

“I can take someone by the hand and walk them through the doorway of their families’ barrack or where their mother taught school, you know, and that sort of passageway to the past is very, very powerful,” Clark said.

Carlene Tinker is one of the survivors who has joined the search. She was at Amache when she was 3 years old. Decades later, she was there when the ofuro was found.

“I remember actually going to and fro with my mom and my two maternal aunts, and ours was way out in the open,” Tinker said. “That water can be used by other people who are also taking a bath. So not only was it a physical activity of cleaning our bodies, but it also, I think of this as a bonding experience between or among all four of us, my mom, my two aunts and myself.”

The ofuro was only one of the discoveries she made during the excavation in 2014.

“I happened to be on the crew that was on the north side. And we were trying to figure out what was in the ground,” Tinker said. “I said, you know, this sounds pretty familiar, Block 11F.”

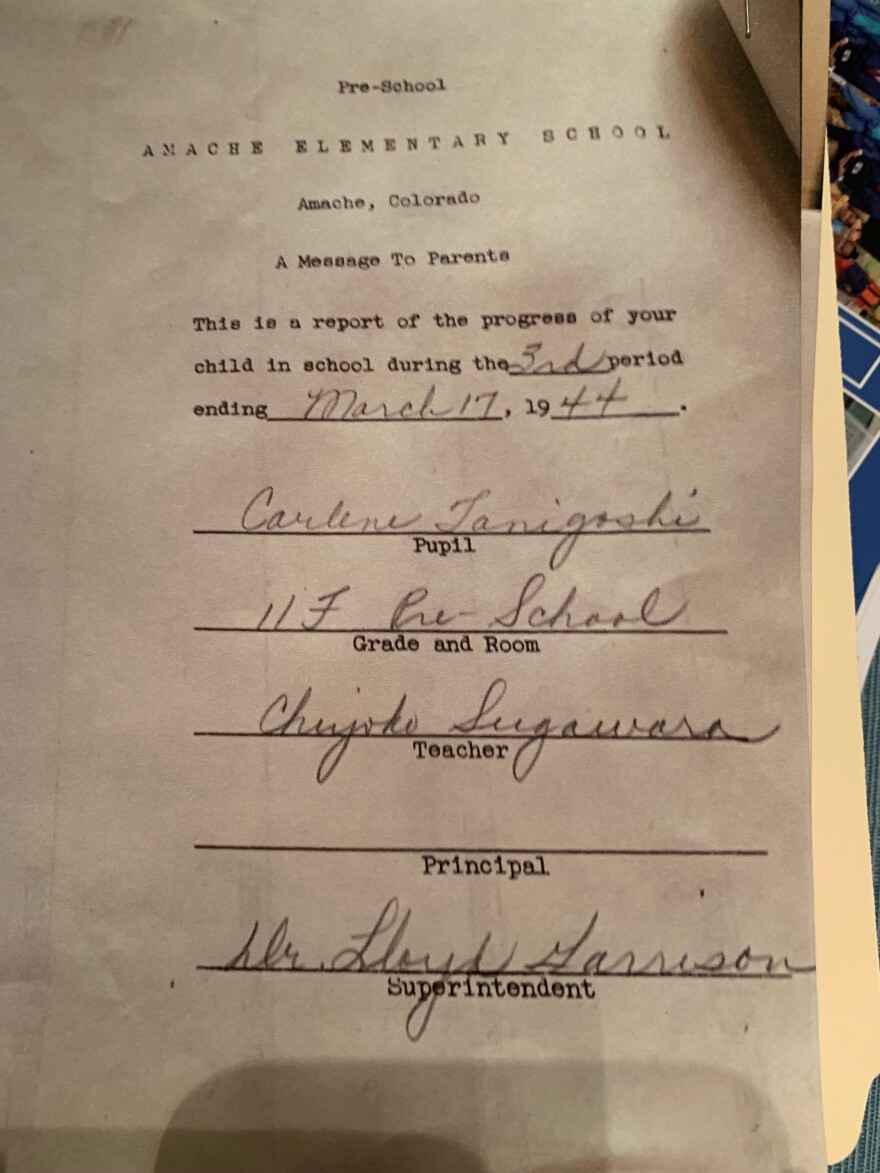

It wasn’t until Tinker visited the National Archives in Washington D.C. that this random excavation meant something more to her. She saw her report card on display – from the preschool in Block 11F.

“And guess what?” Tinker said. “That's how I found out that that was my preschool. … That was proof that I had actually been in that building in World War II from ‘42 to ‘45.”

She helped advocate for the building to be reconstructed. Now, it stands on its original footprint at the site, along with a water tower, guard tower and barrack.

Tinker believes everyone should have the same experience of discovering these pieces of history as she did.

“Every time I go to a field school [excavation], I learn something not only about myself, but also about the hardships and the lives of people who so valiantly survive this experience,” she said. “I think I was delighted that other people would have that same opportunity. And as they pass through, as they would visit the site, they will know more in detail what our story was.”

All these projects make one thing clear to Clark: Experiencing history in a physical way is key to understanding Amache.

“That kind of history is the sort of history that we engage with as like with our whole bodies and not just with our minds,” Clark said. “And I think that's critical for us to be able to, you know, walk in the footsteps of the ancestors.”

Amache will undergo some changes after being put under the umbrella of the National Park Service in March 2022, but seeing those changes could take years. In the meantime, the museum will stay open and the excavations will continue, so Hopper and Clark can keep telling people about a history that should never be repeated.

Coming in Part 3: How National Park Service recognition will affect efforts to preserve Amache

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2022 KUNC. To see more, visit KUNC. 9(MDA1MTkyNjA1MDEyNzM1MTQ0ODk3NTA1NA004))