Sad to say, on any given day, you may see caustic, denigrating or even “wicked” remarks in comment sections of posts on Facebook, X, TikTok, or other social media platforms. But try to imagine the same type of anonymous, yet “wicked little letters” arriving in your mailbox.

And think about what it might have been like it it occurred in the 1920s in a sleepy seaside village. In fact, it did happen; it sparked a huge scandal. A criminal trial followed and the event was even debated on the floor of the British Parliament.

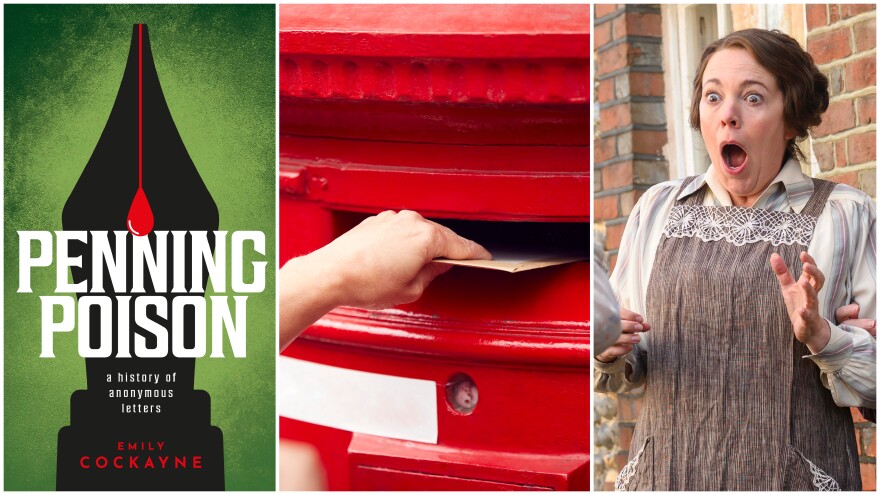

This true, R-rated jaw-dropper is the foundation of the new film Wicked Little Letters, starring Oscar-winner Olivia Coleman. It’s also the big part of a must-read chronicle, Penning Poison, published by Oxford University and penned by Dr. Emily Cockayne, scholar at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich, England.

“It was a series of strange, obscene letters sent between neighbors,. said Cockayne. “It was a jaw dropper.”

But who was accused, convicted and sent to jail, versus who truly was the guilty party is an even bigger stunner.

Cockayne visited with Morning Edition host George Prentice to talk about her very unique scholarship and her work on one of the most-anticipated movies of 2024.

Read the full transcript below:

GEORGE PRENTICE: It's Morning Edition. Good morning. I'm George Prentice. For many, writing, especially handwriting, a letter is a lost art. While some romanticized the idea of receiving a letter, we were recently reminded of how awful actually some letters can be. Which brings us to the new must-read book, Penning Poison A History of Anonymous Letters. Dr. Emily Cockayne is here, associate professor at the University of East Anglia in Norwich. Her research spans modern English, social and cultural history, and this morning she joined us from across the pond in the UK, where it is already afternoon. Dr. Cockayne hello.

DR. EMILY COCKAYNE: Hello, George.

PRENTICE: I'd like to start, if I may, I'd like to ask you to read a passage of your book, if that's okay, on page 209, beginning with the words "What is an anonymous letter..." could you could you read some of that for us?

COCKAYNE: Sure.

"So, what is an anonymous letter? Ought we to place them in some wider perspective and see them as a competitor for other forms of protest, riot, strike, assault, murder, rather than simply regarding them as the bastard cousin to the signed letter? When anonymous letters were most feared, it was because they might damage reputations by exposing secrets or be interpreted as an expression of animosity and manifestation of hate. But animosity manifests itself in other ways, too. And not every angry person wrote anonymous letters."

PRENTICE: But indeed, a good many angry people did write some anonymous letters, which this wonderful book chronicles, and we learned that the writers range in class and profession from all corners of society. Are there any common threads? Uh, what might these letters have in common?

COCKAYNE: I think what they have in common is just what they induce in the recipient. So a sort of sense of bewilderment and confusion, and I don't know the sense that somebody knows where you live and they've sent you something that that they surely know is going to unsettle you in some way. And they've perhaps threatened to expose some of your secrets. And also, it's that tangible, real thing that's entered your house and you kind of think, well, you know, therefore it's got a hint of threat, even if it's not a directly threatening letter, because something somebody knows who you are and where you live, and they have some sort of a, a beef against you. I think beyond that, I think the motivations for sending are so different that it's hard to it's hard to come to a one idea that combines them all, that doesn't that doesn't focus on the recipient.

PRENTICE: Here in the United States, a new movie is about to open here, Wicked Little Letters, uh, costarring Olivia Colman and Jessie Buckley. And I've been able to see it in advance. I can't wait for others to see it so we can talk about it. But indeed, it is based on a true story the story of Edith Emily Swann, and Ruth Gooding. A story that you know well because you actually have written about this in two books, right? You wrote about this in in in Cheek by Jowl A History of Neighbors and then again in Penning Poison. So what can you tease us with? What is their story?

COCKAYNE: The story is about living in close proximity and neighborhoods and therefore knowing each other's secrets, getting to know each other so well that animosities develop and, uh, strange obsessions develop. And I think this is something quite common to neighboring generally, particularly if people are sort of stuck in very close proximity. That means that they can get a sense of those private, secret things. You know, what things people are putting in their recycling or hanging on their washing line start. You start to get interested in neighbors in that way. And these letters, going round Weston Road in Littlehampton from the early 1920s, all have features of this. You know, I know something about you because I live near enough to you to see you moving around and see you doing things. So it's a… it was a series of strange, uh, obscene letters sent between, uh. neighbors in this very sort of tight community, in Littlehampton, which is a seaside town in the south of England.

PRENTICE: It is jaw dropping. The film is a comedy, but I found it to be also heartbreaking and quite serious. And one of these women is sent to prison.

COCKAYNE: Oh, yes. I mean, you know, it is quite jaw dropping. Yes. But it isn't the only case. So there is a very similar case, uh, years before, uh, so in the 19 tens in Redhill. And in that case as, as well, somebody went to prison for longer, uh, was imprisoned for a longer period. Who, um, who was innocent of writing the letters? So, um, this is something happening that's very strange in, uh, in these communities in the 1910s and the 1920s. But what I think is particularly odd is the complete obsession of the newspapers and the police if there is a female suspect. So that's what comes through in the cases that we suspect women are doing things, they're writing naughty letters or threatening letters, and they shouldn't be doing that. So there lies a little bit of interest for me.

PRENTICE: The few folks I have talked to who have seen the film have told me to the person that they find it very relatable, in that in today's era, our technology almost allows even more anonymous poison pen letters.

COCKAYNE: Yeah, I so like the below the line comments on websites and tweets and contact that comes through the internet. It's similar. It's definitely similar to these things. But I think it's also different. So um, let's go back to this idea of shame that you might be tapping into if you write an anonymous letter to somebody and put it through their door or put it in the post, and that's what then it's seen as being published. So this is why these letters are libelous as well, because they're published by putting them in the post. Well, it's that sense that this is something that is written by somebody who knows where you live and has sent something material through your door online that is different, because you still could have a sense that they know who you are, but they don't know how to actually get to you. So in some ways it's less threatening, but also it's more shaming because more people have access to these internet comments. They can be put out to anybody who can see them. So if you receive a letter, you could decide, well, I'll burn that. I'll destroy it because I don't want people to. Maybe there's a grain of truth in the letter, or maybe you don't want people to think there might be, but online you can't do that so much. You have to block and stop these things coming in the first place. Kind of anticipate that they might be coming in.

PRENTICE: Reading your book Penning Poison, which details poison pen letters between the years of 1760 and 1939. I learned in your book why you ended there; but I think it would be important for you to share with our audience why you did end that chronicle in the late 1930s.

COCKAYNE: Because of, again, going back to this idea of shame and secrets that are exposed in the letters. And I kind of thought if I stopped around 1939, then I would avoid re-exposing victims of the letters to, uh, some of this sense of an invasion of their privacy. So I also I also kind of got that there's, there's a lot of letters around about 1939, and it felt as though the body of the letters might take the focus away from other periods of time, because suddenly this welter of information out there, there's certainly in like ten, 20, 30 years’ time, room to write, penning poison mark to picking up again in 1939 and and running with it through time. Um, but at that at the time I thought, well, I really do want to focus on the odd things that are occurring from the late 18th century to the mid 20th century. And to go further, I would start having to look at, uh, telephone details and then hence the internet, internet afterwards. And I really wanted to keep it to this handwritten letter, correspondence, correspondence, although correspondence is probably the wrong word, because correspondence would mean that somebody writes to somebody and somebody writes back. And this is where these letters are very unusual because you don't have the ability to write back to the person. So I thought to focus on the things that I was really interested in, like threats and tip offs and obscenities and libels. I should stop it at 1939. And you know what, as well, I thought I'd get slightly less attention from oddballs who might be, uh, who might be writing letters after 1939 if I were to include them in the book as well. So maybe there's a little bit of cowardice there, too.

PRENTICE: I want to take note of the chapters in this book include "Gossip, Tip-offs, Threats, Obscenity, Libels, Detection, Media," and more. By the way, I was surprised to learn that the term "poison pen" comes from North America.

COCKAYNE: Yeah, it does. So it was popularized first in Maryland, and then it was picked up in Britain. And it was it really has become connected to like these spinsters who write letters, these angry, bitter women who write letters. But I think that is also wrong. That's a sort of, uh, the way that the media can put a spin on these things as well. So, it's interesting. It comes from a newspaper. And then it was developed into, uh, usage, uh, much more common usage. But yeah, it's um, it's not got as older an older heritage as we might think it has.

PRENTICE: Did someone and I forget who... but did someone give the advice that the best thing to do with a poison pen letter is to burn it?

COCKAYNE: Oh, lots of people often said that. So yeah, the police would often say, you know, the judges and the police often come across as quite annoyed in these cases. They sort of say, we get these letters all the time. Why are you paying attention to them, particularly the judges, um, and coroners and people like that. So, uh, and also vicars, vicars would often get a lot of letters because again, these are people it's really easy to write to. You don't really even need an address. So, um, you can get a letter to those people quite quickly, quite easily. And they are losing a bit of patience with people through the 19th century and the 20th century, because to them this is very common. What they're forgetting is they get letters to their workplace and these letters that we are focusing on, the the poison pen letters, they go to people's houses, which is a distinctly different thing. It's a sort of, you know, that's where you should be private. That's where you should be protected from these sorts of, um, invasions in your privacy. So, uh, yeah, some people said burn them, some people said burn them. And then there's a poet that I end the book with who says, well, he's a vicar as well. He says, turn them into poetry. So, you know, pick up the ideas in them and weave them into delicious poetry. And I kind of thought that was a nice way to end the book, because I think that's a lovely idea.

PRENTICE: I want to make sure I have this right. Did I read that you were asked to be a consultant on the film Wicked Little Letters?

COCKAYNE: Yes. So because I broke the story of the Little Hampton Letters in my 2012 book, and I'd been working on it since 2009. I was the historical consultant for the film. Yeah.

PRENTICE: What was that like?

COCKAYNE: It was. It was... it was a hoot. It was really enjoyable. It got me thinking a lot like historians watch films. They watch television. And we just always complain. We sort of say, well, that isn't accurate. There should be more, uh, of this or less of that. And it didn't quite happen like this. And I realized being involved in the film, I literally had no idea about things like the narrative arc and the way that you can get people interested in a story and the fact that you can't pursue exactly the same details, like so. In the Littlehampton case, there are four, uh, court cases. And I swiftly began to realize quite how to get this across to audiences. You couldn't make an audience sit through four court cases, so you distill those ideas and you, um, compress them and you make them into one court case because then the the audience is, is going to stay with you and stay engaged. And so I learned a huge amount about how to put ideas across to, to a different public, to the sort of public that I was used to. And I really I was really quite my my eyes were very open to that. And I'm a lot more forgiving now when I watch anything historical on films and televisions because because it's sort of like, well, yeah, you you can't make people sit through a 28 hours developing the character of someone like Napoleon, for example. So you've got to do this quite quickly for a film. And, and that's, that's a skill that a lot of historians, I think would lack.

PRENTICE: I am excited for people to see Wicked Little Letters, but I'm equally excited for people to read Penning Poison. Congratulations on this. And she is Dr. Emily Cockayne at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, Britain. Dr. Cockayne, great good luck to you. Congratulations on this book. This film, I'm sure, will get everyone talking for all the right reasons. And thanks for giving us some time this morning.

COCKAYNE: Thank you. Okay. Goodbye, then.

Find reporter George Prentice on Twitter @georgepren

Copyright 2024 Boise State Public Radio