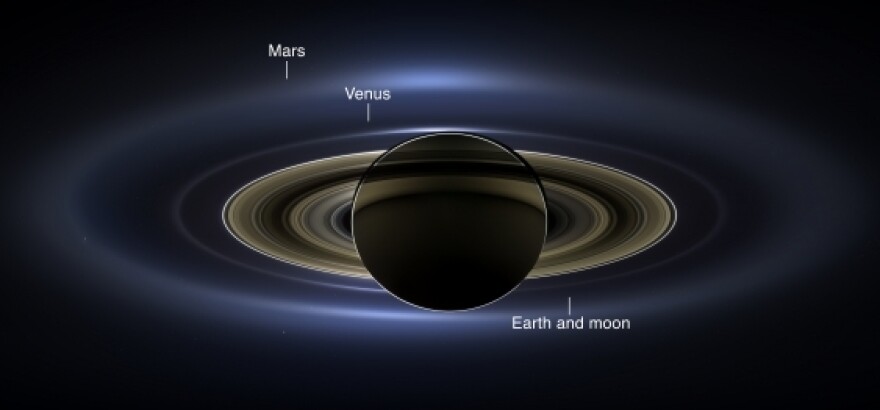

The picture below is the planet Saturn and its rings back-lit by the sun. It’s essentially a planetary eclipse. Earth appears as a blue pinprick in the background. The picture is a mosaic of 141 different images. It comes from the Cassini space craft and it’s getting a lot of attention online.

Matthew Hedman is one of the people most responsible for this picture. He’s an assistant professor at the University of Idaho. He came to the U of I a few months ago from Cornell University where he’s worked on the Cassini mission since the craft reached Saturn nine years ago. There are other U of I people who work on Cassini, but Hedman helps plan what pictures to take and how to take them.

The other part of his job is examining the finished pictures to learn more about Saturn’s rings. And Hedman says they’ve learned a lot.

“We’ve now seen objects striking the rings, basically little comets and meteorites crashing into the rings,” Hedman says. “With that we can start getting a sense of how many little objects are running around the outer solar system which we didn’t know.”

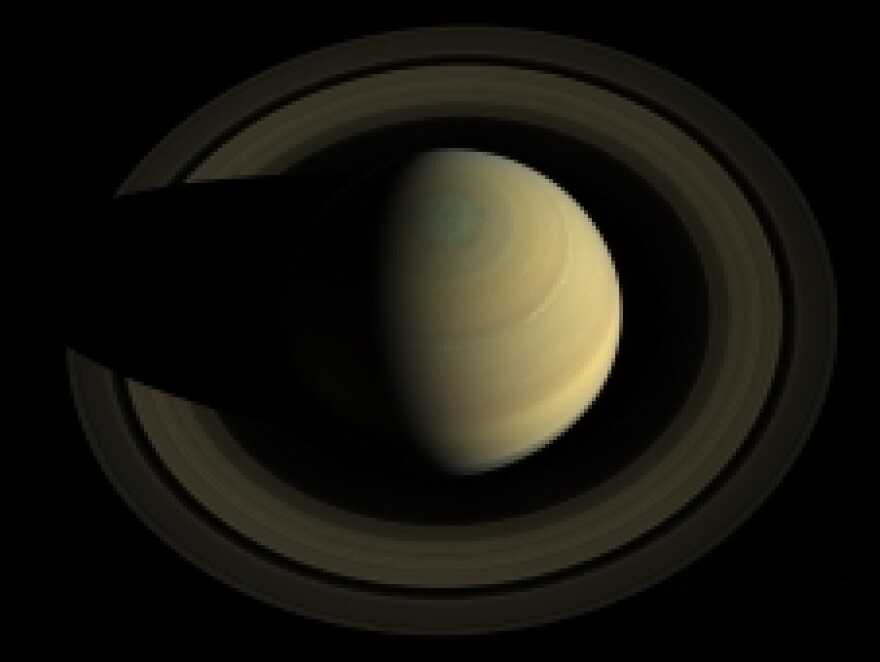

He says before Cassini arrived, science didn’t know how dynamic Saturn’s rings are. They’re composed of billions of chunks of ice constantly bumping into each other and being pulled around by the gravity from Saturn’s moons. They’ve even found tiny “moonlets” embedded in the rings.

But he says much about Saturn’s rings remains unexplained. He says they still don’t know how and when they came into existence.

Hedman says Saturn’s rings are one of the most remarkable things in our solar system. They’re hundreds of thousands of kilometers wide but only a couple of meters thick. For a scale model you’d need a mile-wide disc of notebook paper. He says the Saturn system is so strange that sometimes when people see pictures from Cassini they don’t think they’re real.

He says part of that is the bizarre optical tricks the rings can play. Light goes through them in some places and bounces off in others for example.

“I think partially it’s just it’s a really alien world and system,” Hedman says. “All of our background intuition about how stuff should be, doesn’t necessarily apply.”

He says that’s especially true of the recent picture that’s getting so much attention online. He thinks it’s the most surreal and beautiful one to come from the mission so far. And he thinks when he and others at the U of I and around the country have had time to study it, it could be the most valuable to science.

Copyright 2013 Boise State Public Radio