Logan Miller is scanning the forest floor, looking for signs.

We’re not too far from the city of Hailey, on a popular trail, as mountain bikers whiz past us. We step off the path when Miller spots a scattering of bones in the brush.

“You see how this has been broken, how the bone has been snapped?” he said. “Wolves' jaws are powerful enough to break bone.”

It might have not been a wolf that made this kill, he said, but maybe one came by and checked out the leftovers.

He scribbles in his notebook and takes down the GPS location. He does this whenever he sees a clue – a track, some scat, signs of ungulates and other prey. He’s trying to piece together where the wolves are hanging out.

Miller is a field technician for the Wood River Wolf Project, a Blaine County-based nonprofit started in 2008. The year before, a pack of wolves made the valley their den site. The “Phantom Hill” pack, as they were known, captured the attention of locals and tourists. But when sheep arrived in the valley to graze that summer, the wolves killed several of them and a livestock guard dog.

Fearing the wolves would be killed as a result, an environmentalist, a rancher and an agency official came together and advocated for non-lethal methods to be used instead. Then they got to work, trying to prevent further depredations.

That coalition was the basis of the Wood River Wolf Project, which is now in its 14th season.

The organization’s goal is to use no-kill methods to prevent wolves from killing livestock, in an effort to achieve coexistence between predators and humans.

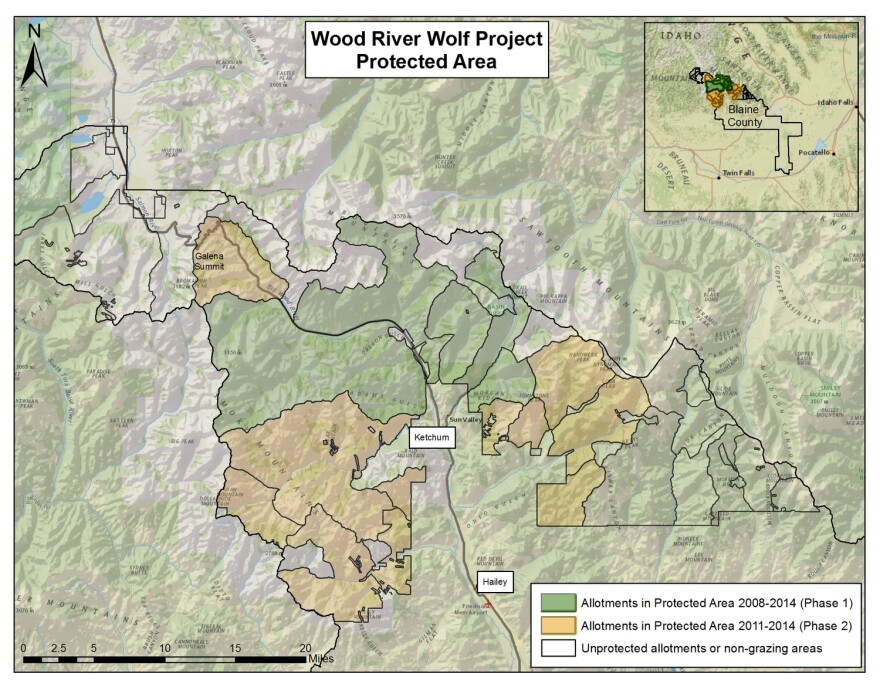

The Wood River Valley is one of the most historic sheep ranching spots in the country and is one of the last thriving sheep grazing corridors in Idaho. Each summer, when four ranchers bring their herds, totaling around 20,000 sheep, up to the mountains to graze, Miller helps keep the animals safe from wolves while they’re in the project area, which spans 463 square miles in Blaine County.

It’s late May, and a wolf pack was spotted in this part of the valley recently. Miller has returned to set up a wildlife camera and to do a “howling survey.” After climbing far off-trail and sitting still for more than an hour, he stands and lets four full-belly howls to the north, south, east and west. He hears nothing back.

Miller gets a return call about one in every 10 howling surveys; he said he heard one last week. It’s the best clue he can get to help him prepare for when the sheep arrive in the forest.

“That's a good indication, okay, something's going on right here,” he said. “I might not be able to find the exact little drainage that it's at. But I can keep sheep away from that area.”

Now, some of the sheep herds are in the project area for the summer, so Miller’s job is different during this time. He sets up the herders with a kit of non-lethal tools — air horns, flashing lights, protective collars for guard dogs — and communicates with them about wolf sightings.

Using his early-season intel, Miller might know of “problem spots.” It’s especially important to keep the sheep away from den sites, he said, where the wolves would be especially protective of their pups.

In those areas, the Wolf Project might encourage bands to pass through quickly. Depending on the forest allotments, they might be able to slightly adjust the grazing course. Other times, that’s not possible and Miller camps out with the herders to add another human presence.

“Just making sound and flashing lights to scare wolves away,” Miller said.

The project aims to prevent depredations from happening in the first place so ranchers don’t need to call the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services to kill the “problem” wolves. And it’s seen results.

About three-and-a-half times more sheep were killed outside the project area than in the project boundaries where non-lethal methods were used, according to a study published in the Journal of Mammalogy in 2017.

Since the organization formed over a decade ago, only one wolf has been killed in the project area, according to its founders. The organization's methods have been studied by scientists and applied overseas.

Yet the Wood River Wolf Project is an outlier in Idaho. The new wolf legislation, SB 1211, that went into effect this month greatly expands wolf hunting and trapping opportunities and allows private contractors to kill wolves that are depredating on livestock. The bill was drafted by the livestock industry.

“We want more tools in our shed,” said Sen. Van Burtenshaw (R-Terreton), who introduced the bill, during a committee hearing. “I don’t think anybody understands depredation better than those that are being depredated against.”

Miller thinks the new policies could have implications for the Wolf Project’s work. He said more wolf hunting will inevitably break up packs. And without a cohesive unit, they might not be able to go after traditional prey, instead opting for easier targets, like livestock.

That theory has been supported, but also challenged, by research.

Then, there’s the precariousness of Miller’s own safety, now that wolf hunters are allowed to hunt at night and use night-vision technology if they have a permit.

“It's not really the most comforting feeling to be doing a howling survey when you think that there's someone out with a night scope, potentially shooting at the sound of wolves from across the valley,” he said.

Cory Peavey, the sheep manager at Flat Top Ranch in Carey and a fifth-generation rancher, is one of the producers who works with the Wood River Wolf Project. He was initially skeptical of its methods.

“I wasn’t convinced that a few flashing lights and proverbially banging pots and pans was going to make any kind of difference,” he said. “My experience with wolves is that they’re problem-solving animals. They’re very brave, and if they’re determined to get a free lunch, they’re going to get it.”

But he said he’s had success with being part of the project, and working more closely with the staff in the last five or so years.

“If you implement things that change,” he explained, “if you move a pickup, if you light a fire, if you move lights around, something for them to fixate their curiosity on, it’s enough to inspire caution in the wolves.”

Peavey has even tried things outside of the project. He’s shifted his lambing and grazing season back to avoid confrontations with coyotes when they’re in the desert.

He’s also participating in a pilot study with a USDA researcher who will monitor if putting flashing lights on the ears of his sheep will deter predators. When the first band of about 1,000 goes onto the forest allotments later this month, 400 of the sheep will have motion-sensitive lights – Peavey calls them “circus tags” – affixed to their ear tags.

Making these changes is risky for Peavey, he said, because the lights could stress the sheep out and that could affect their growth, or make them more susceptible to predators. But, he’s willing to experiment for a larger good.

“I guess I’m young and I’m a risk taker,” he said, “and I see the potential benefit as being worth it, so I take that risk.”

The Wolf Project reduces some of the risk because it pays for Miller’s position and all the gear it gives to the sheepherders.

While it’s historically been common for ranchers to have guard dogs or cowboys to protect their cattle and sheep herds, many do not believe non-lethal methods can solve their depredation problems.

Idaho’s Wolf Depredation Control Board was created in 2014 to distribute and manage funds to address wolf depredations in the state, and has dedicated about $600,000 a year for lethal control. When the Idaho legislature made the board permanent in 2019, industry groups opposed the inclusion of the phrase “non-lethal” to accompany “lethal” in the description of the board’s role.

“We support all means of controlling wolves,” said Wyatt Prescott, a lobbyist for the Idaho Cattle Association. “But when you have an animal depredating and causing a problem, it’s not a long-term solution that we want as a livestock industry to commit our resources to.”

Jennifer Sherry, a wildlife advocate at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council, said lack of institutional support is, in part, why the use of non-lethal methods is not as widespread as it could be.

“These larger funding structures that have been in place for so long have incentivized these reactionary lethal approaches instead of the more proactive efforts to prevent conflict,” Sherry said.

That’s why the organization advocated for, and helped secure, $1.4 million from the federal budget in each of the past two years, for Wildlife Services to conduct non-lethal management projects in 12 states.

In Idaho it means Wildlife Services Director Jared Hedelius has been able to post three range rider positions. They ride horses alongside cattle to protect them from predators. Two range riders started last year in the Mackay and Rexburg areas.

“I reached back out to the livestock producers, and said, ‘Hey, I've got this funding available. Are you interested’? And they all were instantly, ‘Yes, absolutely, we want them to come back,’” Hedelius said of the ranchers who worked with the riders last year.

He said one more position is open in Blaine County, but it hasn’t been filled. He hopes the funding for this program continues.

But not everyone is fully on board. Steve Smith, a Custer County Commissioner, ranches near Mackay. The Copper Basin is vast country, he said, and the rider can’t be everywhere at once. He said, at best, it will be a “small positive.”

On the other hand, he thinks Idaho’s new wolf legislation will help bring the population down and prevent depredations.

“Year-round taking some wolves down, that's going to make a difference,” he said.

One scientific review of efforts to reduce the number of predators depredating on livestock found lethal control is not synonymous with fewer depredations – it even has the potential to increase the number of livestock killed. The study also noted not all non-lethal interventions are evidence-based.

Smith thinks the new range rider positions are only meant to appease environmentalists who are against the direction the state is taking on wolf management.

But, so far, Wildlife Services’ non-lethal projects have been successful, according to Julie Young, a research biologist at the National Wildlife Research Center, Wildlife Services’ research arm.

In three states that hired range riders, only five cattle were confirmed to be killed by predators across 700,000 acres, fewer than were reported the year before on the same landscape, she said.

Part of the new federal appropriation was set aside so her team could study its results.

“Because of the funding, we're able to monitor that and figure out where we need to still do better,” Young said. She said while some non-lethal techniques are well-studied, there’s still opportunity to collect more data and to better quantify the tools that do seem to work on the ground.

Still, even ranchers who are using a plethora of preventative techniques like Peavey say they’re just one tool in the toolkit for reducing conflict with predators, and lethal methods need to be included, too.

“I’m not interested in removing any tools from the toolkit,” he said. “But I will try to deploy them responsibly and try to avoid an issue like that. But come to it, yeah, I will defend my livelihood. I will.”

Peavey knows coexistence is important to his community and the valley where his sheep pass through. So, he said he’ll continue to try all the non-lethal methods he can, as long as they’re working.

Find reporter Rachel Cohen on Twitter @racheld_cohen

Copyright 2021 Boise State Public Radio